Tiling Light

Stardazed supports 3 types of lights: directional, point and spot lights. These are the basic types of lights supported by most, if not all game engines. Up to recently SD had a hard limit of 4 active lights at any time. The light information was stored in a couple of uniform arrays.

I limited the number to 4 initially as all lights were processed for every pixel in the fragment shader, whether they were likely to affect the pixel or not. SD currently only has a forward shader where you process all lights every pixel (or vertex) in a normal render pass. In a deferred shader each light is rendered separately and is usually limited to a section of the screen by enabling the scissor test and clipping rendering to the area of the screen affected by the light.

Another issue is that there’s a limit on the number of uniform vectors available for use during any one draw call and especially on mobile that limit is quite low. The limit is quite easy to reach with a bunch of lights and other uniforms competing for the same space.

Tiled Shading

I had read an article about an implementation of a tiled light rendering pass in WebGL. A student project by Sijie Tian, it is a nice proof of concept of a technique that allows both forward and deferred shading paths to work with a very large number of lights with good performance, provided that the number of lights covering any area of the screen isn’t too large.

In typical scenarios, a level has many lights, but most of them only affect a small area of the map and, depending on the viewing angle, only a couple of lights will affect any given part of the screen, even with many lights in close proximity to each other. Tiled lighting exploits this by dividing the screen up into a grid of square areas and determining before the actual lighting passes are run which lights affect which parts of the grid. Inside the lighting code, a lookup is done in the precalculated grid to get the list of lights that affect the current pixel. So even if many lights are active, the fragment shader will only process the ones that are likely to affect the pixel being processed.

Implementation

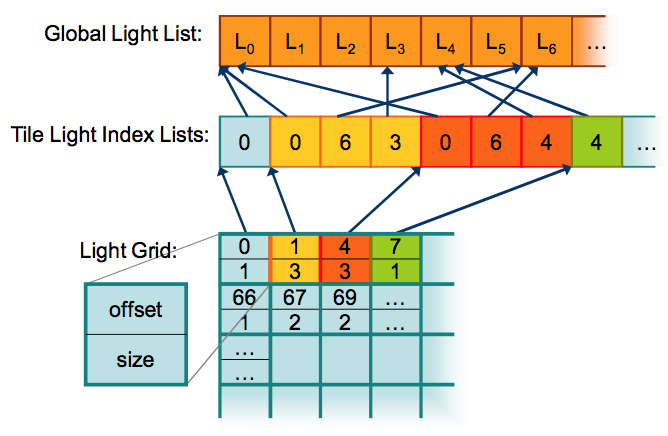

Mr. Tian based his implementation off of a paper by Ola Olsson and Ulf Assarsson from 2011 that explores Tiled Shading and details the pros, cons and possible ways to implement it. I decided to use it as a starting point as well. Modifying the lighting code was actually quite easy. Most of the fiddly bits were once again reading the grid and light info from a texture, like in my vertex skinning code. I used the data structure as suggested in Olsson’s paper as shown here (image taken from the paper):

The Global Light List is a mostly static array containing the properties of the lights (position, type, colour, direction, shadowing, etc.) In SD, this list directly represents all of the lights in the scene. The Light Manager component operates directly on the data in this array.

The Tile Light Index Lists is a packed list of variable length lists of indexes into the Global Light List. Each sublist contains the indexes of the lights present in a tile of the Light Grid. This data is updated every frame and will vary significantly as the camera moves through the scene.

Finally, the Light Grid is a grid of cells representing a low resolution view of the viewport. Each cell in the grid represents a 32x32 square on the viewport. The paper by Olsson and Assarsson states that both 16x16 and 32x32 tiles worked out well. Since SD has to generate the grid every frame in JS code, I opted for the 32x32 grid as it reduces the numbers of cells by a factor of 4. The size of the grid is locked to the viewport size % 32 so during normal operation, the size is fixed.

In the Light component, these 3 structures are all stored in a single 640x512 4-component float texture. At startup, a Float32Array is created on the client and is subdivided in 3 layers:

The first 256 rows of the texture are assigned to the global light list. Each light entry takes up 5 vec4s, which was the main reason to have a width of 640 texels, each row can store 128 lights exactly. Given this, SD has a limit of 256 * 128 = 32768 dynamic lights present in a scene, which should be enough for now.

The next 240 rows are assigned to the tile light index lists. Since each list entry is just a single index, I place them together inside the texels, one index in each component. This allows for 640 * 4

- 240 = 614,000 active indexes in any given frame.

Because WebGL 1 does not allow a vec4 to be indexed by a variable, I had to add a set of conditionals in the data lookup code as shown below. This is only done once for each light index access so it hopefully should not add too much of an additional load on the shader. WebGL 1 only allows for simple, mostly constant accesses into arrays and basic flow control.

float getLightIndex(float listIndex) {

float liRow = (floor(listIndex / 2560.0) + 256.0 + 0.5) / 512.0;

float rowElementIndex = mod(listIndex, 2560.0);

float liCol = (floor(rowElementIndex / 4.0) + 0.5) / 640.0;

float element = floor(mod(rowElementIndex, 4.0));

vec4 packedIndices = texture2D(lightLUTSampler, vec2(liCol, liRow));

if (element < 1.0) return packedIndices[0];

if (element < 2.0) return packedIndices[1];

if (element < 3.0) return packedIndices[2];

return packedIndices[3];

}The light grid is stored in the final 16 rows of the texture. Each cell taking up 2 components so each texel stores 2 cells. So again, I can store 640 * 2 * 16 = 20,480 cells. Each cell represents a 32 x 32 rect on the screen, so even a retina 5K fullscreen viewport (5120 x 2880) only needs 160 * 90 = 14,400 cells. Given that most WebGL apps run (by necessity) in a small viewport (like 720p), this should suffice for a while.

Given a more typical 1280 x 720 viewport with 920 cells, the current max of 614k indexes allows for an average of ~639 lights per cell, way more than reasonable. Of course, right now the texture size is fixed at 640 x 512, but I’m planning to add smaller versions as well for simpler scenes to have as little wasted memory as possible. By having the rows allocated for each structure be variable as well a very efficient lookup table can be created for scenes with a known number of lights.

Since the table is calculated on the CPU and only a small part is changed every frame, the GPU texture data is updated by determining which rows in the 3 tables are affected and only sending those to the GPU.

Building the Light Grid

As noted above, every frame the light grid and tile light index lists have to be updated. Currently, only point lights are projected, spot and directional lights are just added to every cell in the grid. The point light loop conceptually works as follows:

- for each point light

- calculate an (approximate) area on the viewport that the light will affect

- for each (partial) cell in the light grid covered by the area

- add the light’s index to the cell

- flatten the tile indexes into one long array

- store the offsets and counts in the grid

The projection is made by calculating the 8 vertices of the cube enclosing the full range of the light in worldspace. Each point is then projected into screen space and the 2D rectangle that encloses all of the projected points is the result.

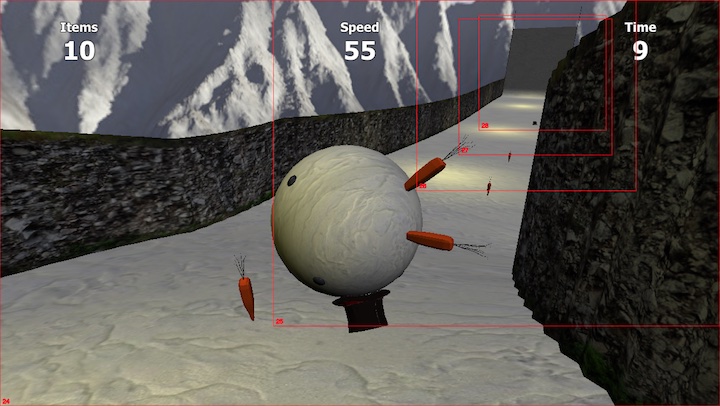

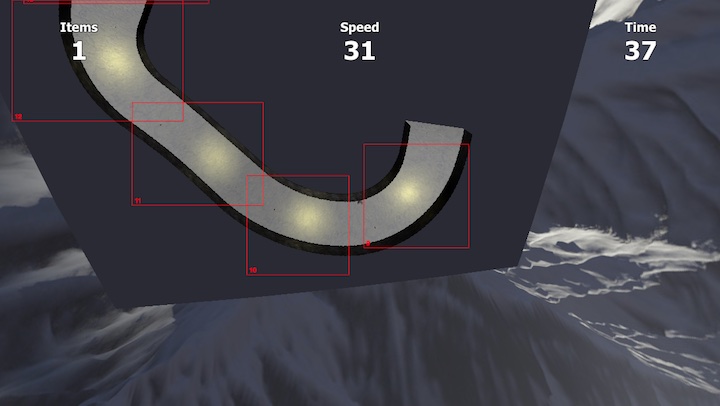

I used my older LD34 entry Snowman Builder Extreme to test the code that projects the lights onto the viewport. The game is simple but has a nice sequential series of lights that are easy to mentally map onto the screen as well. The following screenshots show the state as of then:

And another from a debug birds eye view:

I’m not satisfied yet with the rect calculation and there are some issues to work out, but this was good enough for my current LD entries so I moved on.

Optimizing the Light / Grid Loop

The conceptual light test code above can be rather heavy if done with many arrays, flattening and concatenating them, so I took a different approach. I split the work into 2 blocks, as shown by this pseudocode:

interface LightGridSpan {

lightIndex: number;

fromCol: number;

toCol: number;

}

// ...

function updateLightData() {

let gridRowSpans = Array<LightGridSpan>[gridHeight];

// create a list of 1D spans for each row in the grid per light

for (light of pointLights) {

let screenRect = projectLightToScreen(light);

let gridRect = screenRectClampedToGridDim(screenRect);

for (row = gridRect.top to gridRect.bottom) {

gridRowSpans[row].push({

lightIndex: light,

fromCol: gridRect.left,

toCol: gridRect.right

});

}

}

// iterate over each cell in the lightgrid, filling the tile index lists

// and populating the grid.

let indexOffset = 0;

let gridOffset = 0;

for (row = 0 to gridHeight) {

let spans = gridRowSpans[row];

for (col = 0 to gridWidth) {

// append the light index for each applicable span to

// the light index list

for (span of spans) {

if (span.fromCol <= col <= span.toCol) {

tileIndexLists[indexOffset++] = span.lightIndex;

}

}

// write the offset and count of the tile indexes used for

// this cell to the grid

lightGrid[gridOffset] = (cell index offset, cell light count);

gridOffset += 2;

}

}

}Even though the second block has several nested loops, it traverses the grid data linearly once and iterates over the relatively short span list each cell, and the span list is updated only once per row.

Future Work

As it stands, this works quite well but I took some liberties here and there as part of the code was written during a Game Jam. I will want to have spot lights also projected to either a rectangular area or a cone on the screen (the spans array can represent arbitrary shapes, so that was a happy accident.) The actual calculation of the areas also needs to be cleaned up, it now has some fuzz factors applied to make it work.

It worked out quite well for my LD37 entry, Callisto, where I was able to have about 30 point lights in a single room all calculated dynamically without any real trouble on most hardware.

Oh right, light maps. Need those too.